Silent Grouping: Better than Kevin Spacey

Everyone understands the importance of being able to predict the future. And as software teams, we’re asked to do this a lot. Like it or not, there’s any number of stakeholders working with, or affected by, your project, and one of the things they’re going to be particularly concerned about is the delivery date. It’s an inevitable part of the software development process. Sometimes, they’re the people paying for it. Sometimes, they’re the people marketing it. Sometimes, whether you get paid or not depends on it.

Unfortunately, in this world of agile and scrum and kanban and waterfall and kanbanterfall and all of the other wonderful software project methodologies, you’re going to run into the tension between the certainty of a delivery date, and the certainty that you don’t know enough to make that call. And, not getting into the whole ‘estimation is a myth’ debate (that’s for another article), for the sake of argument today I’m going to acknowledge that there are a number of ways to predict the future, and that some of them may be more accurate than others.

Story pointing is a pretty long-held method of predicting the perceived effort involved in the delivery of a feature, and is often the tool used to extrapolate those estimates into a delivery date, on the basis of historical trends in your team. The idea is that we start with the smallest estimate for the smallest feature we can think of, and then everything else is estimated in relation to this: so, changing the colour of a button may be a ‘2’ (2 means nothing), whereas changing the size and position of that button may be anywhere from a ‘3’ to a ‘100’ (again, the number means nothing) depending on complexity. If we don’t have enough information to assign a perceived ‘effort’ against a ticket, or if the estimation we have arrived at is too big, we go back to the drawing board, breaking the feature down further where we can, and gathering enough information in order to be able to decide on how much effort we think the ticket might take.

The idea is that the numbers you assign inherit meaning as your workflow becomes established within the team: after a prolonged period of time, you team can get so accurate at this (and so familiar with their own process and ways of working) that ‘2’ can subsequently translate to 3 days from development to completion of a feature for example. There’s a lot of negatives to this, and lots of teams make the mistake (and it is very easy to do so) of directly equating points to time way to early in the process – but if you can do it right, it can become a reliable method for working out how long things might take to build.

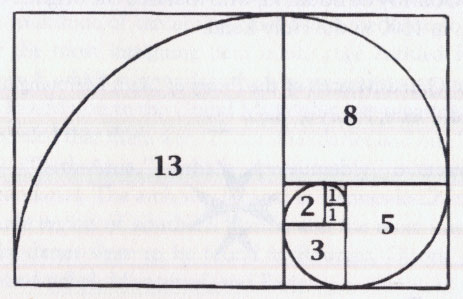

Arguably the most prevalent method for doing this is planning poker. Planning poker involves a deck of cards, each marked up with a ‘points’ estimate on a scale (estimation traditionally runs off the Fibonacci scale, so the order goes 1,2,3,5,8,13,20(sometimes),30,100 and so on). Each member of the team (and this exercise should involve everyone from the project, so all disciplines) gets a set of cards containing each number.

The tickets for estimation are taken in turn, and the feature or problem we’re trying to solve is presented to the team. Once the feature has been explained, and any kinks or edge cases deemed important are nailed down in terms of approach, everybody plays the card they think reflects the effort it would take to complete the feature. If the numbers played don’t match, further discussion happens, and further hands are played until an agreement on estimated effort is reached. Points as mentioned are arbitrary, but any points assignation should be done based on previous experience. If you have none, it’s guess-work; and it should be widely known by all stakeholders that even if we’re guessing to begin with, this isn’t wasted effort – it’s a vital part of establishing a benchmark against which you’ll work in the future.

This exercise is incredibly useful, in that it allows people of all levels of experience to outline what they think the challenges inherent to a ticket will be – and it means that an estimate isn’t arrived at based on one team members’ experience, because we want to remove as many dependencies from the process as possible; what if the team member who estimated the ticket isn’t available to do the work, and someone else has to pick it up for example?

However, planning poker requires discipline; often these meetings can last several hours and can quite easily diverge into technical implementation discussions, wider product ambition discussions and so on, and the longer they last the less likely your estimates are to accurately reflect the work as attention wains. Estimation sessions, if not tightly controlled, can often become seen as a bit of a chore and a waste of time – and the more people involved (which by rights there should be to ensure a balanced set of views are represented), the more expensive they become.

So, how can we make this process just as accurate, but shorter and less time-consuming for everyone involved? Another approach to try (that in my experience works particularly well) is called ‘Silent Grouping.’

Silent grouping (i’m not going to lie) looks a bit weird. The basic idea is that all of the tickets you want to estimate are stuck to a great big whiteboard in an unprioritised column. Next to this are a further series of columns, split by your estimation flavour of choice – this could be time, points, t-shirt sizing, kittens, whatever you use. Each ticket should have the story detail associated with it to enough of a level that everybody should be able to understand the task at hand.

At the beginning of the session, the tickets are outlined by the BA/PM and any obvious questions or edge cases/considerations are nailed down to ensure everybody understands the work required for each of the tickets. Once this briefing is complete, the entire team lines up in front of the board. From this point forward it is absolutely essential that no-one speaks. No discussion should be had between now and when the exercise is completed.

One by one, each team member picks up a ticket (in any order from the batch of tickets) and places it in the column that they think most accurately represents the work involved in the task. The person taking their turn can also elect to move a ticket that has already been assigned an estimate if they feel the estimate already given doesn’t reflect the work involved. This process is continued in multiple cycles until all tickets are assigned to a column on the board, and tickets are no longer being swapped from column to column.

The beauty with the process of silent grouping is that removing the discussion element from the process has a threefold impact:

- It’s fairer. Teams are made up of a wide range of personalities, and it can become easy during a traditional planning poker session for the loudest personality to dominate the discussions. Silent grouping removes this element, allowing each person to silently contribute their opinion, affording equal weight to everyone.

- It improves accuracy. Removing the discussion element allows people to focus on the tasks for estimation personally. Any feature we build involves a multitude of complex processes, and during a traditional estimation session it would be impossible to cover all of these in detail as a group – there’s just too much to consider. Silent grouping allows each member of the team to consider each ticket individually and from their own perspective, and as such it usually results in a more well-rounded consideration of both the task at hand and any potential pitfalls that may arise

- It can save time. Surprisingly enough, and probably as a direct consequence of point (2), silent grouping disagreements over the weight of a ticket often sort themselves out in a couple of cycles. The fact that each person can consider tickets individually and without input from other team members means that each person can come to their own conclusions about the reason behind a disagreement, and challenge themselves to determine why someone else may consider a ticket bigger or smaller than they would. This can neutralise any lengthy debate process that can often arise in a traditional planning poker session, making the process much quicker.

Although the process sounds like it may be a lengthy one, it’s been consistently suggested that once silent grouping is embedded as a process within a team, it can reduce the time taken to estimate stories significantly to a fraction of what it takes to complete a traditional planning poker session, whilst simultaneously improving accuracy. The fact that the process is accelerated also means that an estimation session can become something the team actively looks forward to, rather than becoming a source of dread.

So, silent grouping – remember, if you’re going to have to predict the future, it’s best to do it quietly.